Nighttime on Still Waters

Nighttime on Still Waters

The Christmas Eves of Childhood

You are invited to join us for a very special episode as we celebrate Christmas Eve onboard the Erica and remember the Christmas Eves of our childhood.

Journal entry:

21st December, Thursday, Winter Solstice

“The year’s turning

And the longest night.

There’s a rough wind

And angry skies.

The polestar oak

Finally felled.

The ducks don’t seem

To notice."

Episode Information:

Can I take this opportunity to wish you a very MERRY CHRISTMAS and a happy NEW YEAR!

With special thanks to our lock-wheelersfor supporting this podcast.

Rebecca Russell

Allison on the narrowboat Mukka

Derek and Pauline Watts

Anna V.

Orange Cookie

Donna Kelly

Mary Keane.

Tony Rutherford.

Arabella Holzapfel.

Rory with MJ and Kayla.

Narrowboat Precious Jet.

Linda Reynolds Burkins.

Richard Noble.

Carol Ferguson.

Tracie Thomas

Mark and Tricia Stowe

Madeleine Smith

General Details

In the intro and the outro, Saint-Saen's The Swan is performed by Karr and Bernstein (1961) and available on CC at archive.org.

Two-stroke narrowboat engine recorded by 'James2nd' on the River Weaver, Cheshire. Uploaded to Freesound.org on 23rd June 2018. Creative Commons Licence.

Piano and keyboard interludes composed and performed by Helen Ingram.

All other audio recorded on site.

Become a 'Lock-Wheeler'

Would you like to support this podcast by becoming a 'lock-wheeler' for Nighttime on Still Waters? Find out more: 'Lock-wheeling' for Nighttime on Still Waters.

Contact

- Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/noswpod

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nighttimeonstillwaters/

- Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/noswpod.bsky.social

- Mastodon: https://mastodon.world/@nosw

I would love to hear from you. You can email me at nighttimeonstillwaters@gmail.com or drop me a line by going to the nowspod website and using either the contact form or, if you prefer, record your message by clicking on the microphone icon.

For more information about Nighttime on Still Waters

You can find more information and photographs about the podcasts and life aboard the Erica on our website at noswpod.com.

JOURNAL ENTRY

21st December, Thursday, Winter Solstice

“The year’s turning

And the longest night.

There’s a rough wind

And angry skies.

The polestar oak

Finally felled.

The ducks don’t seem

To notice."

[MUSIC]

WELCOME

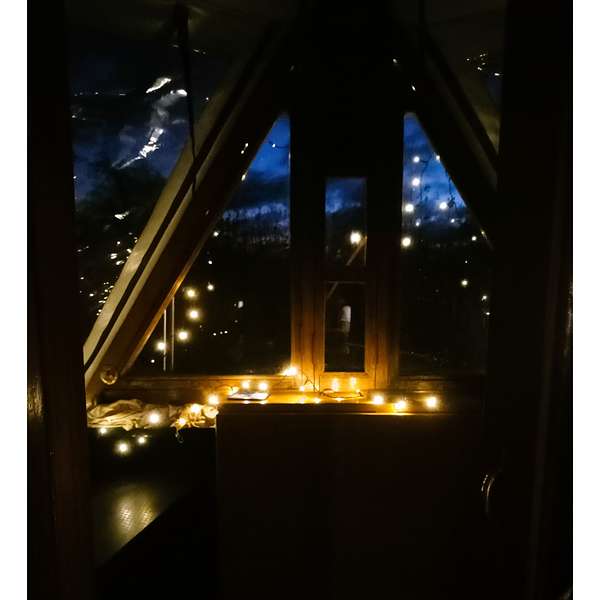

It is another windy night that buffets the boat and makes the alders roar. But Christmas is almost here and this is the narrowboat Erica narrowcasting into the darkness of a special night to you wherever you are.

I am so glad that you could join us as we celebrate Christmas Eve here aboard the Erica. So, come inside, make yourself comfortable beside the stove, while I get the drinks. Welcome aboard.

[MUSIC]

THE CHRISTMAS EVES OF CHILDHOOD

It’s Christmas Eve on the canal - not that you could tell it that much. The ducks go about their squabbling ways, pushing through the water with puffed out chests. The swans preen and forage. The moorhens dart, chitter, and flick along the waterside. All the time above them, the jackdaws hooligan and riot on black-caped wings while the rooks look down long beaks and read the fields for worms. It could be any eve, of any year, but it’s not, and all the while I wait for the skies to break open with angelic song to flood the world with golden light and dressing gowned shepherds with unconvincing beards and baby lambs draped around their shoulders as if they were feathered boas to feign mock surprise and wonder, and for the convocation of trees at the top of the hill to burst out in a trumpet swell of jubilate and gloria in excelsis deo. For behind that cloud. That big cloud, mushrooming and battleship grey, a great star shines, and caravans of wisemen, ride the sea-like hills and vales on purse-lipped camels, and when they pass, if they ever do, there will be a glint of gold, and the sheep field will swim with the smell of sheep-droppings, fox musk, and the sharp scent of frankincense and myrrh. And of course, I wait for the sound; the sound of Christmas Eve. The rich hymning sound of bells and all that is warm and alive about Christmas. The rafter-raising chimes of steeple rocking church bells, cantabile carillons in the bat dancing hush of holy darkness, that roll like musical thunder over the rooftops of sleeping villages. But most of all, I listen for the tiny cat-bell ring of sleighbells, distant, thin, and as fragile as icicles.

And around me tumble from the brooding sky all the Christmas Eves of my past falling silently in the great shaken snow-globe of my mind; great moth-like snowflakes, fat and feathery, each heavy with a sharp-sweetness and half-forgotten dreams of laughter and torch-light. And the memories gather round me like old friends, as comfortable and as welcoming as old slippers. Soft they fall those Christmases of my younger self. Those old Christmas Eves of long, long ago.

Oh yes, I remember… I remember.

I remember how, in those days, Christmas was such a long time coming. Each Christmas took an eternity of waiting. The agonising expectation of how many more sleeps yet to go? When December broke, we were nearly there. We were on the downward roll by then. Each never-ending day ticked off by the solemn ritual of peeling open of the paper advent calendar door to reveal a little picture printed in primary colours and slightly out of register. These were the days before advent calendars dispensed chocolates or little gifts. Festive pictures (if you’re lucky), sprinkled with glitter, that stuck to stubby finger tips or showered upon the carpets in a snowstorm of brittle stardust.

However, the countdown had started long before that. At school preparations were already well underway. Christmas presents and decorations were crafted from toilet rolls, shiny coloured foil that flashed and shone magic under the fluorescent classroom strip-lights, coloured tissue paper that tore if you sneezed and stuck to wet fingers, and lots of cottonwool snow. And there were blunt rounded-ended scissors that bent and ripped the coloured sugar paper and old tissue boxes, but could never cut it and great white plastic bottles of Copydex that smelt of ammonia (Grizzer said it smelt like the pigs’ pee on his farm!). It dried on our fingers and knuckles in leprous scabs and, if you rubbed your hands together really quickly, it turned into little rub balls which you could flick like bogies with one finger at Julie Tricker because she had pig tails and was pretty, and the teacher would tell us to “Stop it” and to get back to our work, and we’d look outside the window at Christmas falling out of the grey sky like angels and snowflakes. Slowly our hand-made Christmas decorations would emerge from the catastrophe of cutting and off-cuts. An anaemic Santa rudely drawn and rudely coloured with pencil stubs and wax crayon grease, sticking at an odd angle out of a toilet roll chimney covered in whisps of Copydexed snow and billows of cottonwool smoke. Another year it was a table decoration of pine cones covered with glitter of shocking colours. Once we made our own Advent Calendars in the shape of a Christmas tree. Twenty-four clumsy and wonky hand-drawn, exuberantly coloured, parcels that you could peel open to reveal more pictures hidden underneath. But what is the point of an Advent Calendar that you could know what the hidden picture would be? My pencils never behaved anyway and little red toy steam engines looked like a red stack of bricks smoking the dog-end of a cigarette, and the snowman looked like carrot sticking out of a number eight.

Yes, I remember Christmases of long, long ago. Shake the snow globe and make it swirl, Leicester Square and Piccadilly, turn the world of Santa Claus white. And these days, from this blizzard the flakes fall not so much as distinct memories of each Christmas, but, as each perfect snowflake once it falls merges into a magical, iced-ocean of white, so my Christmases of childhood, meld and merge into one sweeping landscape. But they’re no less warm or magical, or filled with light, for that. Yes, there are flashes, gem-clear, of finding a lumpy pillowcase at the foot of my bed, and with a feeling of unbelief, running my fingers over the jumble of shapes in the darkness. Tiptoeing out of bed to turn on the light and finding a parcel that I could tell was a book and silently opening it so as not to wake anyone. There were two books, one on space exploration, one on mountain climbing. Alternating pages of pictures and writing. And in the hushed Christmas pre-dawn of a waiting morning, I sat up in bed and climbed the Matterhorn and Mount Everest. Yes, there are lots of fragmented pictures and images, but most of all, it’s the feelings that I remember.

And the aromas. Those special scents forever, wedded to the magic of Christmases past.

Oranges were a rare and special treat in those days. The exotic perfume of satsumas and clementines announced Christmas had come.

And of course, the fresh waxy-tang of pine trees that, if you pushed your head between the scratchy tickle of its branches you could still smell the outdoors on each needle, and reindeer, and snow, lighted igloos.

And then there was hot candle wax and living flame that danced in the hidden breeze that blew in through the window panes, and rubber hot water bottles, and new slippers, and wax crayons, and bath cubes that smelt of lily of the valley and crumbled into chalk between your frog-wrinkled fingers, and sage and onion stuffing. The smell of hot metal and scorched dust when Dad put on the central heating making the radiators gurgle and hiss, and the sharp smell of ear-drops for my constantly troublesome ears, and condensation that beaded down the metal window frames, and the smell of new annuals, with their hard glossy covers. I knew I had grown-up (although didn’t feel it) when I no longer got a comic annual for Christmas.

But that was still in the unimagined future. The world was still young and had more to give.

Christmas was exotic. We had little glass bowls of nuts which never seemed to go down; knuckle-hard hazel nuts, walnuts, and almonds like shrivelled fossils of orange segments, which you had to gnaw the creamy kernel from the broken shells. The bowl of nuts never used to go down. The widow of Zarephath may have had a jug of oil that never ran out, we had bowls of nuts that never ran out. Next to them was kept a metal nut-cracker, of a tarnished silver colour and which left a strange smell on your fingers after using it. Walnuts always beat me. When a grown-up opened one for me, it looked like a little brain and tasted bitter.

Dates too – in lozenge shaped boxes made of thin wood and included a wooden pick that tasted of lollypop sticks. The dates themselves, thick brown and stickily oily. I viewed them with suspicion. They reminded me of tinned stewed prunes that Aunty Kay and Aunty Charlie used to eat for breakfast. They were treats for grown-ups. Although though coloured box wrappers enchanted me with the promise of countries of deserts and oases crossed by caravans of sneering camels, and little cups of thick sweet teas and sultans, and Aladdin, and minareted buildings. Lands that beckoned to me from the far-borders of my imagination.

Food was in abundance. Battenberg – or as we knew it church windows – cake, alongside the Christmas cake and iced sponge that sis and I helped Mum to decorate. We always used the same decorations – often still complete with a wedge of rock-hard icing from the year before, which, when no one was looking, I used to gnaw off like Tilly used to gnaw at her bone. The fact that the Father Christmas in some sort of space rocket and the little girl on a taboggan were far larger than the tree of the pillar-box used to worry me rather.

But it was the savoury things that appealed to me the most. Twiglets! Oh, the unparalleled delight over pushing a thumbnail through the cellophane and open the cardboard lid of the box to inhale the gloriously Marmite aroma of Christmas. Coloured glass baubles, tinsel, and twiglets made my Christmas complete. Actually, twiglets were also a birthday treat too sometimes. One incident forever written into family history was when we had a party in which several of my school friends came. As far as I remember it was the only time that we had one – apart from the ‘in-house’ affairs that I have to admit I preferred. But this year, we all went up to Windsor for a treat, and Graham something or other, ran round Windsor castle with two twiglets stuck up his nose. Dad still goes all white and shaky at the thought of it. But it is Christmas that I always associate with Twiglets. One year, I sucked and licked all the marmite off them and left the twigs on the plate. I can’t remember what Mum said, perhaps it is just as well.

Mum used to serve small shallow glass dishes in which sliced tomatoes and cucumbers were arranged. The cucumbers were my favourite. They were soaked in vinegar and a spoonful of sugar. If I was lucky, at the end of the evening when everyone had gone home, I was allowed to drink the vinegar. Sometimes the sugar had still not completely dissolved and would crunch deliciously vinegary between my teeth.

Shake the globe again, and new snows fall. Snow upon snow. Two children one kneeling, one standing on the window sill of a large bay window waiting for mum to return along the rainy street carrying a Christmas Tree. Holly clipped from the bush beside the coal shed and Mrs. Fuller’s, and decorations dragged in battered cardboard boxes out of the loft and the top of a wardrobe. The needful transformation of home had begun.

There were always packets of balloons. Sis and I would pour them out onto the table like cold rubbery fish, and try to blow them up. I wasn’t very good at it. I could never tie the neck and so they’d fizz and shriek around the living room. We bought them from Kingham’s, the village printers and stationers. We’d also buy from there packs of coloured gummed strips to turn into paperchains, that hung and drooped across the ceiling to entangle the balloons we batted like cats to one another. A lot of the decorations were paper, some of them from Mum and Dad’s childhood. An angel that, when you opened it up, had a white bell-like body of honeycomb paper. A coloured ball, a bell. Sagging tissue-papered concertinas of garlands.

And of course, the coloured glass baubles and tinsel. Dad would wrap the reel of coloured lights, checking each bulb to see if it was securely screwed in. We also had little candle holders which clipped onto the branches. They still contained the malformed wax stubs of old candles. Mum said that they used to have them when she was a little girl. They were added along with the rest of the decorations for old time’s sake. They added a depth of history to the proceedings. We had bundles of tinsel, but there was a shortish length of electric-purple tinsel that was my favourite. It was almost the purple of chocolate wrappers. Over the successive Christmases we grew up together. As I grew taller, it grew shorter and more threadbare. Christmases evolve, they have to because we inhabit them differently. The old Christmases of my childhood diminished in proportion to that small strand of tinsel.

And that is it, when I look back (and forward) at Christmas, it is the waiting, the preparation, the excitement of something different that has, oh so nearly, come. Perhaps that is why Christmas Eve will always be true Christmas for me. The older me shares that same feeling of eager expectancy that the young me felt. It wasn’t about the presents, or, at least, now and for a long while, it is not about the presents. It is about something different, something warm, something filled with light, occurring in the midst of winter’s gloaming. Waiting for Dad to clock off early from work and come home in the afternoon when it was still light. Getting ready to go out to meet up with Uncles and Aunts. Mum had a brother and a sister (both married with families) and we alternated visits over the Christmas period. Christmas Eve was always the most exciting. The drive there was always one of the best parts. Looking at the decorations hung in the lit windows of houses and towns we’d pass, then down the streets and lanes, bordered with prickly tangled brush of winter-brown hedges. Chestnut, and hazel, russet and sienna, interspersed with the skeletal forms of oak, and beech, ash and elm; tangled, like scarecrow hair against the darkening, sleigh-ridden sky. Seeing relations three times in such close succession, must have been a strain. I remember Mum and Dad saying to each other once that the problem is, by the third visit, you’d run out of things to say. Although, us children didn’t suffer from that. It was only later that I realised how hard work it was to find things to talk about it. We were content with playing with each other’s toys. And then there was the television. Both sets of Uncles and Aunts had televisions, colour ones too – when they came out. After our tea, perched on sofas and poufs, or just lying on the floor, we would all sit round it and laugh until our ribs ached and we panted for breath. And the grown-ups would say, ‘how clever it was’ and ‘how do they think up these things?’ Sometimes a band would play – it was just like on the radio, but not quite right. Herman and the Hermits ‘No Milk Today.’ And then one of the older relatives would say, ‘Is that a boy or a girl singing? It is quite impossible to tell these days’, and there would be a general hub-bub of conversation about how different things are now. And Wendy, who was the eldest of us all, would humph.

One Christmas Eve, we watched Apollo 8, listening to the strange almost unearthly voices so far away spoken by the ghosting slow motion figures. I was 8, too old for Santa and his sleigh, but enchantment was still filled the edges of my world. But I had found a new universe filled with stars to replace the old one.

After a while, someone would say about the danger of the kids getting square-eyes, and the television would be turned off. We would all sit and watch the picture disappear into a little dot in the middle of the screen – a bit like the USS Enterprise from Star Trek in reverse. And there was a moments silence as if the world around was too embarrassed to make an entrance and was hiding in the corners.

"Who wants to be Father Christmas?" one of the uncles would boom, and the world once more was filled with colour and noise. Presents swapped under the tree were then handed out.

Shake the globe one last time.

Bundled up against the cold, two sleepy children clutching their new toys or books led to the car for the drive home. Ah, yes, I remember that well, too. The slight smell of engine oil and cold vinyl of the old minivan. KMF 301B. The rattling purr of the engine. The hiss of tyre on wet road. The sporadic click, click, click of the indicator. Wendy and I would stare out of the windows into the sky. One year, one of us, I can’t remember who, said, “Did you see it?”

“What?”

“In the sky. A sleigh and reindeer. Over there.”

Neither of us believed it really, but I thought I might have seen something. Flying meteor-like fast, silver against black, high up where Telstar and the satellites orbited. I could, of course have been wrong, but I did swear I could hear sleighbells.

And the dark world sped passed us, Christmas trees and coloured lights in lit windows. The old landmarks – the coloured lantern that hung outside the house on the blind bend, the signpost that stood on its little green triangle of grass, the old gnarled oak tree whose trunk jutted into the road. The church where ghosts and bishops in pointy hats and shepherd crooks slept. Dozing, waking at the shift in gear or slowing down for a junction. Too tired to open eyes. The soft comforting rattle and hum of the car and murmur of voices in the front. I wonder what Father Christmas will bring? Dozing again, heavy head curled onto the back seat. Click, click, click. A shift down in gear, slowing. Then a swinging turn into the entrance of the garage. Waiting for the longed-for but awful click of the ignition key. And the sudden all-encompassing silence as the engine stopped. Knowing I'd have to open my eyes, get up, move. Time to get up and walk up the steps to the front garden and home. Bed seemed so far off.

It didn’t snow much in the Christmases of my childhood, but I don’t remember it ever bothering me. I could imagine whisps of snow among the whorl of starlight following Santa’s sleigh in a sky of royal blues and indigo. But I do remember that it did once. I must have been small. I can remember opening my eyes to see smooth sugar drifts of waves covering the garden and flower beds that sparkled in the street light and Dad scooping me up in his arms and carrying me up the garden path. I can remember thinking that it was Christmas. The rattle of key in lock. The front door swinging open. The smell of conifer and hot water bottle. I was being carried into Christmas.

SIGNING OFF

This is the narrowboat Erica signing off for the night and wishing you a very restful and peaceful night. Good night.